Why Young People keep leaving Greece? 🧠✈️

A brief analysis of main metrics provided by OECD data, exploring and summarising while sharing some personal thoughts on the economic situation of Greece which leads to brain drain.

February 16, 2022

Introduction

As I recently relocated to a northern European country from Greece, the instances in which people that I met have asked me what led me to the decision to emigrate have been numerous.

You see, most if not everybody is familiar with the Greek crisis of 2009 and the events that unfolded the following years. Still, many people are also under the impression that this is mainly history. Hence, when you state that there are no opportunities in Greece and wages are not sustainable, most of them seem surprised and have many more questions.

This was also the case a few weeks ago, as a new friend of mine, Daniella from distant Peru, bombarded me with questions about Greece and its economy. I have to say that while I tried my best to answer her questions straightforwardly, I think that at the end of the night, she probably had even more. This sparked my mind with the idea of exploring the most updated available data about Greece.

I hope exploring these data will shed some light on our conversation and answer her questions and the questions that I think many other Greeks and I often receive. In the end, anyone can make up their own conclusions.

Quick Notes

For the purpose of this analysis, I will use data only from Countries within the European Union as most Greek immigrants etc., are located and working in other European Countries and not at least so much in Costa Rica or Mexico, for example, who are also OECD country members. United Kingdom, USA, Canada, and Australia will also be included as there are a lot of Greeks located and working in these countries.

The full list of Countries that will be included for the analysis and the graphs will be the following: Austria, Belgium, Czech Republic (Czechia), Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Slovakia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, United Kingdom, United States, Canada and Australia.

Data Overview

📌 Unemployment rate : The unemployed are people of working age who are without work, are available for work, and have taken specific steps to find work.

Development of the unemployment rate metric over time for Greece.

📌 Unemployment rates by education level : This indicator shows the unemployment rates of people according to their education levels: below upper secondary, upper secondary non-tertiary, or tertiary.

📌 Long-term unemployment rate : Long-term unemployment refers to people who have been unemployed for 12 months or more.

📌 Employment rate by age group : The employment rate for a given age group is measured as the number of employed people of a given age as a percentage of the total number of people in that same age group.

📌 Self-employment rate : Self-employment is defined as the employment of employers, workers who work for themselves, members of producers’ co-operatives, and unpaid family workers.

📌 Hours worked : Average annual hours worked is defined as the total number of hours actually worked per year divided by the average number of people in employment per year. Actual hours worked include regular work hours of full-time, part-time and part-year workers, paid and unpaid overtime, hours worked in additional jobs, and exclude time not worked because of public holidays, annual paid leave, own illness, injury and temporary disability, maternity leave, parental leave, schooling or training, slack work for technical or economic reasons, strike or labour dispute, bad weather, compensation leave and other reasons. The data cover employees and self-employed workers. This indicator is measured in terms of hours per worker per year.

📌 GDP per hour worked : GDP per hour worked is a measure of labour productivity. It measures how efficiently labour input is combined with other factors of production and used in the production process.

📌 Average wages : Average wages are obtained by dividing the national-accounts-based total wage bill by the average number of employees in the total economy, which is then multiplied by the ratio of the average usual weekly hours per full-time employee to the average usually weekly hours for all employees.

Focusing on insight

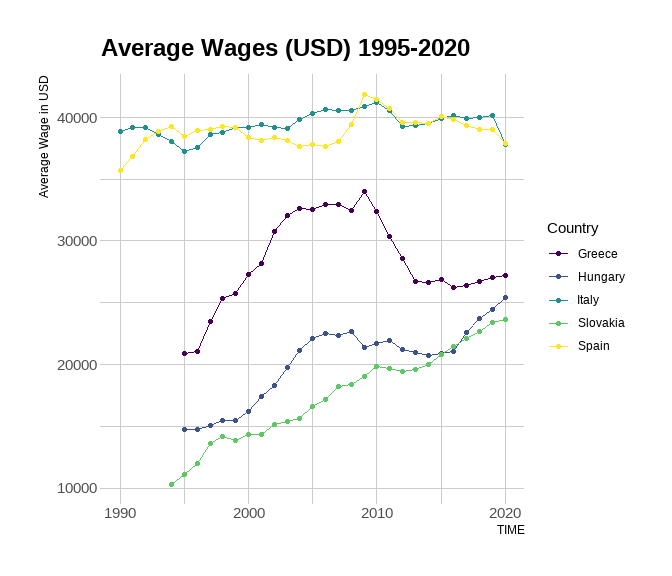

According to the OECD available data, the average wage for Greece peaked at 33.974 US Dollars in 2009. The latest available data of 2020 show an average wage of 27.207 US Dollars, a decrease of 19.9% in the national wage average from its peak.

From the countries we are exploring, this is the most considerable decrease in the national average wage, with the second place in most significant decrease going to Spain with a national average wage decrease of 9.45%, from a peak of 41.883 in 2009 to 37.922 USD in 2020. Italy seems to come third with a decrease of 8.3%. Almost all of the other countries considered in the analysis have not seen a decrease in their national average wage from their respective peak. Furthermore, their national average wages are increasing steadily over the years, with most of these countries reaching their peak during 2020, where our available updated data end. This is also the case for Hungary and Slovakia, the only two countries with a smaller national wage average than Greece as of 2020 data. While they have a lower national average wage, their average wages are steadily increasing over the years.

📌 Gross Domestic Product (GDP) : Gross domestic product (GDP) is the standard measure of the value added created through the production of goods and services in a country during a certain period. As such, it also measures the income earned from that production, or the total amount spent on final goods and services (less imports). While GDP is the single most important indicator to capture economic activity, it falls short of providing a suitable measure of people’s material well-being for which alternative indicators may be more appropriate.

Summary

A summarized look in table form to get a holistic view of key metrics.

Conclusion

On a personal note, from my own experiences and knowledge, the opportunities (limited to none) and the working conditions that exist in Greece are very much indicative of what one would expect from a country with these metrics.

However, raw data do not always draw the complete picture of a situation, but a lot of the time is a close imitation of reality.

This reality leads many people, particularly young people, to the hard decision of leaving home and, in this case, their home country. The reasons are always unique for each individual. The feeling, mostly the same for everyone.

Growing up as a child, you think you have to follow the natural flow of the societal norm and rules to “succeed.” Go to school, go to university and then find a job. Easy, right? This is not the case for many young people in Greece, though, as they would be naive to live by that thinking. After they are done with their studies, they have to face a deep cultivated and crisis-enforced environment of nepotism, further amplified by unemployment and stagflation.

Furthermore, these studies take place in universities with extensive curriculums considering the international and European norm of three-year bachelor programs. Thus, students are often prisoners of unnecessarily prolonged study programs that make academic field transitions not an option and the average graduation age inflated. Moreover, Greek Universities and education have been depreciated and academically devalued in every ranking as education spending has swamped along with the rest of the economy. As such, this makes Greek graduates less employable in the broader international job market, where what you studied does not matter as much as where you studied, in a battle of prestige and not substance. A job market which anyway values degrees faintly and only for the very early stages of one’s career, since degree inflation is as prominent as ever and thus formal education is less likely to make the difference in landing a job.

In addition, men have to undergo one year of compulsory military service, further extending the time they start their career or just pausing their career and putting a hiatus to their development.

All of those mentioned above and the data presented are even more significant and relevant in a market where seniority and competence is measured in tenure years. A job market that is based on an experience-centric snowball effect, leaving those who enter the race late to finish panting. In the finance market, they have the saying “Time in the market beats timing the market”, and perhaps the same can apply to the contemporary labor market.

Is it time for young Greek adults to return, or are more of them leaving home?

You may feel like home is the anchor in your storm, but leaving may well save you from drowning. ~Unkown

The data that I used for the graphs and tables are available from the OECD organization. The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) is a unique forum where the governments of 37 democracies with market-based economies collaborate to develop policy standards to promote sustainable economic growth.

All of the graphs and tables included in the post are my own work created with R code. The code is available on my GitHub account.

For attribution, please cite this work as:

Why Young People keep leaving Greece? 🧠✈️ .

Michalis Zouvelos. February 16, 2022.

mzouvelos.github.io/blog/why-young-people-keep-leaving-greece

Licence: creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0